|

| (c) XKCD |

For some inexplicable reason, I have always struggled with grammar and spelling. In elementary school, my mother and my teachers could not comprehend how I could read and understand thick novels grades above my reading level but couldn’t pass more than half of my spelling tests.

Over the years the severity of these deficienceies has decreased significantly, but there are still little things I have major trouble with. So for both my edification and yours, here are three of my grammar enemies in no particular order:

Commas:

My LEAST favorite punctuation mark, bar none. To this day I still don’t actually know most of the rules, I just put a comma wherever I naturally pause in a sentence. That, however, is not always the right place to put a comma.

Because the rules regarding commas are numerous (seriously. THERE ARE SO MANY!), I’m just going to provide some good, detailed references for future… um… reference.

Fanfare for the Comma Man

The Most Comma Mistakes

Rules for Comma Usage

Why Commas Matter

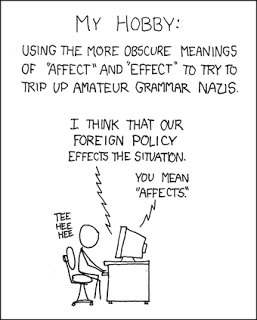

Affect/Effect:

Does it matter? Really?

Don’t say anything. I already know it does. But that doesn’t make it any easier for me to remember which is which. But that’s when I pull in outside sources! According to Grammar Girl’s Quick and Dirty Tips:

It’s actually pretty straightforward. The majority of the time you use affect with an a as a verb and effect with an e as a noun.

When Should You Use Affect?

Affect with an a means “to influence,” as in, “The arrows affected Ardvark,” or “The rain affected Amy’s hairdo.” Affect can also mean, roughly, “to act in a way that you don’t feel,” as in, “She affected an air of superiority.”

When Should You Use Effect?

Effect with an e has a lot of subtle meanings as a noun, but to me the meaning “a result” seems to be at the core of all the definitions. For example, you can say, “The effect was eye-popping,” or “The sound effects were amazing,” or “The rain had no effect on Amy’s hairdo.”

Lay/Lie/Lain/Loon:

Okay, so that last one isn’t part of the sequence. These words still confuse the hell out of me. I usually just pick one at random and hope the little squiggly line of Word’s grammar check doesn’t show up. That isn’t exactly the most efficient way to go about this.

According to this site, these are the simplified rules of usage:

Lie is an intransitive verb (one that does not take an object), meaning “to recline.” Its principal parts are lie (base form), lay (past tense), lain (past participal), and lying (present participle).

[Lie meaning “to tell an untruth” uses lied for both the past tense and past participle, with lying as the present participle.]

Lay is a transitive verb (one that takes an object), meaning “to put” or “to place.” Its principal parts are lay (base form), laid (past tense), laid (past participle), and laying (present participle).

The two words have different meanings and are not interchangeable. Although lay also serves as the past tense of lie (to recline) – as in, “He lay down for a nap an hour ago” – lay (or laying) may not otherwise be used to denote reclining. It is not correct to say or write, “I will lay down for nap” or “He is laying down for a nap.” The misuse of lay or laying in the sense of “to recline” (which requires lie or lying) is the most common error involving the confusion of these two words.

> Once you lay (put or place) a book on the desk, it is lying (reclining, resting) there, not laying there.

> When you go to Bermuda for your vacation, you spend your time lying (not laying) on the beach (unless, of course, you are engaged in sexual activity and are, in the vernacular, laying someone on the beach).

> You lie down on the sofa to watch TV and spend the entire evening lying there; you do not lay down on the sofa to watch TV and spend the entire evening laying there.

> If you see something lying on the ground, it is just resting there; if you see something laying on the ground, it must be doing something else, such as laying eggs.

Hopefully this collection helps someone. I pulled the post together and I’m pretty sure I still won’t remember any of this.